Kevin Hoffman's Blog

Blathering about development, dragons, and all that lies between

Dealing with the Diabolical Distributed Deadline Dilemma

Exploring Problems and Solutions Related to Time Limits in Distributed Systems

Distributed systems are hard. Frameworks that make a distributed system look and feel monolithic makes things even harder.

In this post I want to talk about some of the problems we run into, some of the solutions we often use, and some we might not immediately embrace. As a disclaimer, this post is not a “you should do it this way” post. It’s merely one person’s musings on how frequently his job boils down to solving this problem for yet another application.

First, to set the stage, let’s assume that we need to implement a function in an API gateway The domain for this sample is less important than the interaction patterns with distributed systems discussed in this post. that returns a list of augmented reality objects within sight of a given viewer. Let’s say we’re wearing AR goggles and we perform some action that requests the list of objects.

The code for this might look something like (I am simplifying to avoid cluttering the point of the post):

let objects = api.getNearbyObjects(my.location);

This looks harmless enough, but we all know that far too many mobile applications leave it like this and simply hang indefinitely when something goes wrong or when they don’t get a timely response from the server.

The next natural step is to supply a deadline, like so:

let objects = api.getNearbyObjects(my.location, Duration::from_secs(2));

This gives us a generous 2 full seconds to obtain a list of all the nearby objects. This solves our problem and we can ship our entire product front-to-back, right? Well, pull up a chair, dear reader, grab some coffee, and enjoy the ride because this is about to get all kinds of ugly.

Nested RPC Deadlines

Functions like getNearbyObjects hide an ugly truth. Hidden beneath that function call is an unknown number of other function calls. Within those, yet another unknown amount of child calls, and so on and so on. This execution tree is also likely filled with conditionals where sometimes the code path is long and sometimes it’s short.

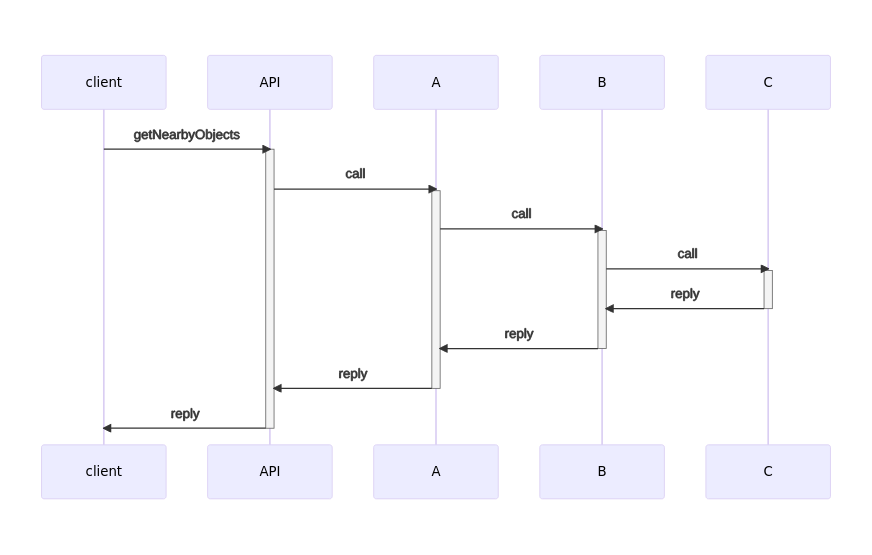

Take a look at this sequence diagram:

In this diagram we can see our original getNearbyObjects call, but there are a large number of calls executing beneath. If we reuse the same timeout for all of our RPC calls, then every single call made beneath the root call will also have a timeout of 2 seconds. This results in a fairly common scenario where the root call quits early because child calls still have remaining deadline in their 2 second budget.

A naive solution to this might be to simply multiply the root call’s timeout by the number of sub-calls we know we’re going to make. So, if there are 11 child calls in the maximum possible code path, then the root call needs a 22 second timeout. In the happy path this doesn’t make a difference, because if everything finishes quickly, we get a result quickly. However, if something bad does happen (and it always does in production), then the caller will wait 22 seconds for a negative result. The caller also probably has a timeout, so it’ll give up early.

While it’s horrible that we might be subjecting a customer to a 22 second timeout, there’s a hidden cost here, too: our backend might still be doing work long after anyone interested in the outcome has timed out. Not only is this wasteful, but if we overlap enough timeouts, we could end up causing more timeouts due to resources consumed processing no-longer-relevant requests! If we do hit this edge case under load, it could spiral uncontrollably until it brings down our entire system.

Circuit Breakers

One strategy for dealing with this problem is to simply give up. Giving up in a controlled fashion allows you to model the failures through your system so that you can predict (and test) the worst possible scenario.

Let’s say getNearbyObjects makes use of two different subsystems in order to get its information. With a circuit breaker if one of these systems is unavailable, we can bypass the attempt to call it and return some reasonable error value

It’s been my experience that explicitly bubbling up “system unavailable” data errors works better than trying to return defaults, empty lists, or nulls. Let the user-facing code decide how to render unavailable data.

.

Circuit breakers work really well to solve the “nested RPC timeout” problem. Depending on what tool or framework you’re using, it’s possible to bypass making calls to dead systems entirely. If a system habitually times out, the circuit breaker framework can immediately return unavailable for some period of time to let the system in question recover.

There’s an infinite amount of room for optimization in the circuit breaker world, and, depending on your needs, you might not need anything more than this. On the other hand, if circuit breakers use timeout values to determine availability, they can also return “false negatives”, and incorrectly block access to guarded systems.

Leveraging Async and Concurrency

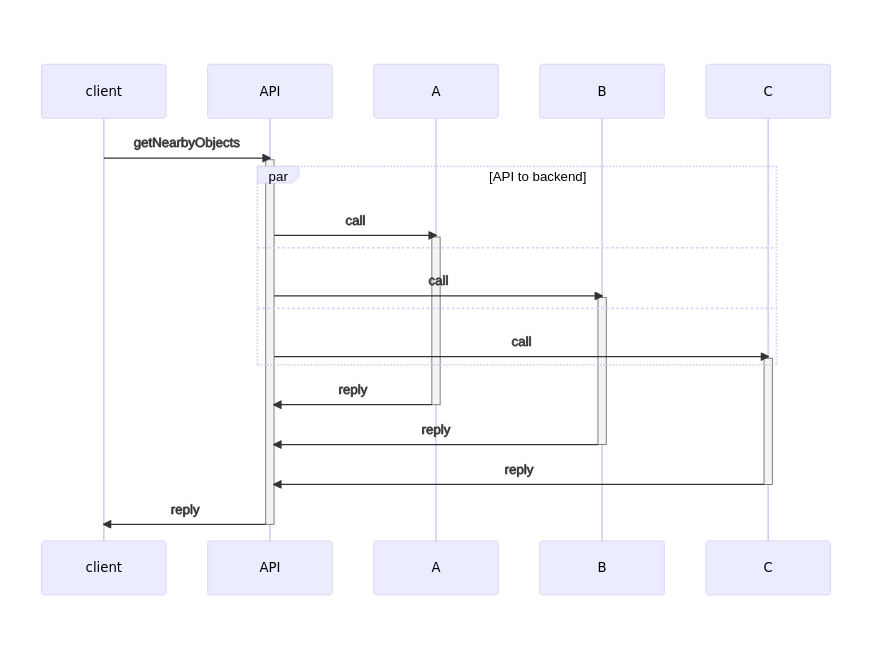

Some of you readers may have been shouting at this post, “Just run the calls concurrently!" This is a routinely used solution to this category of problems. We could refactor getNearbyObjects to make use of multiple subsystems concurrently, as shown in this new sequence diagram:

Each time we split the work into n concurrent processes, we’ve divided the original problem of the distributed deadline into n smaller, parallel problems. So instead of the timeout being calculated as duration * num_processes, instead it’s the timeout used by the longest-running sub-process. The core problem remains, however, it is just smaller.

At this point our problem may resemble one that we can solve with map-reduce or other well-known distributed patterns for which there are open source and off-the-shelf commercial solutions. If we can solve it by leveraging those tools, then we should definitely consider this when evaluating pros and cons. Just be wary of the “every problem looks like a nail when we’re holding a hammer” fallacy. Not everything is well suited to distributed map-reduce, no matter how cool those tools might be.

Deadline Extension Antipattern

Here’s an example of of what (IMHO) we should not do. I’ve made this mistake with distributed systems in the past, and it spreads all kinds of ugly over what might otherwise be a nice setup. This antipattern stems from a desire to hold onto the wrong paradigm for a particular solution, introducing an impedance mismatch between the mental model we want and the mental model we need.

What if instead of assigning fixed deadlines to our distributed RPC executions, we empower all of the various components in a system to request more time? At first blush this sounds like a pretty cool solution. If a particular long-running process is running slowly, it can just ping the “more time” service, which adds to the always-draining pool of time for a given task. Clients simply wait until the time pool expires for any given task.

Here’s the rub: this isn’t really buying us anything, because eventually this chain of elastically expandable deadlines reaches the customer, and there we have a finite amount of time… so we enforce a fixed expiring deadline on top of the elastic timelines of our backend. If executed poorly, we can even re-introduce the problem where our backend is doing work about which our customers no longer care.

Ultimately this pattern adds a tremendous amount of complexity to our back-end for no user-facing benefits.

Component A: I’d like more time to finish up.

Component B: I don’t care. Nobody cares. Nobody likes you, component A.

Component A: *cries*

Event-Driven Solutions

When all else fails, the only logical solution is to make your system reactive (I’m only being a little bit facetious here). Instead of having a request-reply, traditional pattern, the idea here is to send in some request for work into a black-box back end and then await some event or series of events as work completes.

To continue our AR example, we could submit some stimulus into the back end, like some command named DiscoverNearbyObjects on behalf of the user. Then, immediately as each nearby object is discovered, this could result in ObjectDiscovered events that are piped to our customer. As each object is discovered, it can be added to our augmented reality canvas and overlaid on the camera view.

An additional optimization could be made such that we split the discovery events for an object and its details (like model, mesh, AR properties, etc). This would let us spawn an indicator for a “loading” object so that user knows something is there, and we’re waiting to find out what it is. Whether this pattern improves or detracts from UX is a matter of some debate.

We could be on the lookout for DiscoveryFailed and DiscoveryCompleted events, where the latter might indicate that there are no more pending objects in that discovery request. This doesn’t solve the dreaded distributed deadline dilemma, but it makes most of the timeout deadlines irrelevant to the customer. After some amount of time elapses without receiving certain events, the customer-facing app will need to assume a failure occurred

This approach is particularly prone to the “endless refresh” attack/problem. If you don’t prevent or rate limit requests, they can stack up behind each other and regular customer interaction could quickly turn into a denial of service attack.

.

The point here isn’t that event-driven architectures are a panacea for all distributed systems problems (in fact, sometimes ED/ES can add vast amounts of unnecessary complexity). The point is that if we consider alternative architectures to traditional problems, we might be able to design our way out of a problem rather than coding our way out. Following the path of least complexity may be that yellow brick road we’re all looking for.

Realtime, Streaming Consumer-Facing UX

In keeping with the idea of designing our way out of distributed problems, what if we designed the user-facing portion of our app in such a way that it never actually waited? What if it didn’t care (mostly) about the time it took to complete requests?

While not all domains can support this kind of design, a surprising number of them can be adapted to this approach. Let’s take our AR goggles example. Instead of a specific user action causing a discrete request-response interaction with “the cloud” that has implicit or explicit deadline management, we could instead send a steady stream of our location to the cloud (or, better yet, the closest edge gateway Super cool optimization idea: we know ahead of time a low-res vague idea of where the user is, so we can bind their streams specifically to shards containing the subset of AR objects “living” in that same general area. This could dramatically speed up queries. Want to know a cool way to hash/shard geolocations? Check out Open Location Codes! ) and at the same time receive a steady stream of object discovery and object update events.

In the future when a ubiquitous 3D map/point cloud of most locations in the world exists, we could also stream in collider boxes, meshes, and physics information for our current location, which could inform how all of our AR objects interact with “reality”.

While the AR domain is super inspiring and making me nerd out quite a bit as I write this blog post, the point is that through clever and thoughtful design, instead of increasing the amount of code and complexity we need to support, we might be able to dramatically simplify the way everything works in a way that ultimately benefits our customer.

A strange game. The only winning move is not to play.

The best way to solve a distributed systems problem is not to have it in the first place.

Wrap-Up

Just as the best answer to the question, “how do you do distributed transactions?”, is you shouldn’t, one of the best ways to survive distributed systems deadlines is to not use them.

Deadlines and timeouts in any system of scale are a dangerous proposition. If you get them too high, your customers wait too long. If you get them too small, you chop off work before it’s complete. If you try and predict the best timeout values, you’ll probably be wrong.

Circuit breakers don’t solve the problem, they only limit the blast radius. If you absolutely positively must have timeouts and discrete request-reply patterns, then circuit breakers should be in place as a way to limit/predict the worst-case scenario.

If your domain can support it, the best solution might be to avoid request/response and fixed deadlines entirely, resorting instead to reactive, event-driven systems that react to streams of incoming data and supply that to users when appropriate.

Of course, there is no one size fits all solution. A hybrid of the above options is often found in real-world systems, where some pieces can be reactive and others require request-response NB: You can build a synchronous facade on top of an asynchronous system, but the reverse is not true. .

Finally, after all this bloviation, I’ll sum it all up as follows: before you jump down the rabbit hole of adding infinite complexity to a system, consider ways you might be able to sculpt the UX in such a way that you don’t need that complexity after all. There are real, working solutions to the deadline problem, but none of them are easy.