Kevin Hoffman's Blog

Blathering about development, dragons, and all that lies between

The Ray Tracer Challenge w/Unison - Chapter 1

Implementing chapter 1 of the ray tracer challenge in Unison

I implemented the types and functions in chapter 1 of the ray tracer challenge book.

Finding sample projects that help you learn and explore a language is difficult. If you pick something that’s too easy, you don’t learn anything new. If you pick something that’s too difficult, you get frustrated and (rage) quit.

When I first picked up The Ray Tracer Challenge and looked at the table of contents, I was pleased with how it guides the reader from the simplest foundational elements up to the very hard things. I thought this might be the perfect slope for the learning curve I want for exploring a new language.

In chapter 1, we explore the Tuple, a structure that has an x, y, z, and w element. The first 3 fields should be familiar to most people and the w is either 0 or 1 depending on whether the tuple is a Point or a Vector.

My first problem was figuring out how to model the fact that points and vectors are tuples in a language that doesn’t have objects, inheritance, or even traits/interfaces that let you express an is-a relationship between types.

After a lot of back and forth between me, myself, and I (and again bugging people on the Unison slack), I finally decided to just implement Vector.new and Point.new as functions that return Tuples.

The following is my Tuple type (note that I don’t actually need a discrete type for vector or point, as you’ll see as I show more code):

unique type Tuple = { x: Float, y: Float, z: Float, w: Float }

Now let’s take a look at the functions I wrote to create new vectors and points:

Vector.new: Float -> Float -> Float -> Tuple

Vector.new x y z =

Tuple x y z 0.0

Point.new: Float -> Float -> Float -> Tuple

Point.new x y z =

Tuple x y z 1.0

The math around why you use a 1.0 for a point and a 0.0 for a vector ends up being pretty cool, and makes some calculations in upcoming chapters much easier.

Next, I needed to implement some common vector functions (which work on tuples) like dot, cross, magnitude, and I even got to overload the + and / and - operators! It’s also worth noting that the implementation of normalize calls magnitude.

Vector.magnitude: Tuple -> Float

Vector.magnitude v =

use Float pow sqrt +

a = pow (Tuple.x v) 2.0

b = pow (Tuple.y v) 2.0

c = pow (Tuple.z v) 2.0

sqrt (a + b + c)

Vector.normalize: Tuple -> Tuple

Vector.normalize t =

use Float /

mag = Vector.magnitude t

Vector.new (Tuple.x t / mag)

(Tuple.y t / mag)

(Tuple.z t / mag)

Vector.dot: Tuple -> Tuple -> Float

Vector.dot a b =

use Float * +

((Tuple.x a) * (Tuple.x b)) +

((Tuple.y a) * (Tuple.y b)) +

((Tuple.z a) * (Tuple.z b)) +

((Tuple.w a) * (Tuple.w b))

Vector.cross: Tuple -> Tuple -> Tuple

Vector.cross a b =

use Float * + -

Vector.new ((Tuple.y a * Tuple.z b) - (Tuple.z a * Tuple.y b))

((Tuple.z a * Tuple.x b) - (Tuple.x a * Tuple.z b))

((Tuple.x a * Tuple.y b) - (Tuple.y a * Tuple.x b))

The operator overloads for + - * and / all apply generally to tuples, so the overloads are part of that type:

(Tuple.+): Tuple -> Tuple -> Tuple

(Tuple.+) a b =

use Float +

Tuple (Tuple.x a + Tuple.x b)

(Tuple.y a + Tuple.y b)

(Tuple.z a + Tuple.z b)

(Tuple.w a + Tuple.w b)

(Tuple.*): Tuple -> Float -> Tuple

(Tuple.*) t factor =

use Float *

Tuple (Tuple.x t * factor)

(Tuple.y t * factor)

(Tuple.z t * factor)

(Tuple.w t * factor)

(Tuple./): Tuple -> Float -> Tuple

(Tuple./) t factor =

use Float /

Tuple (Tuple.x t / factor)

(Tuple.y t / factor)

(Tuple.z t / factor)

(Tuple.w t / factor)

(Tuple.-): Tuple -> Tuple -> Tuple

(Tuple.-) a b =

use Float -

Tuple (Tuple.x a - Tuple.x b)

(Tuple.y a - Tuple.y b)

(Tuple.z a - Tuple.z b)

(Tuple.w a - Tuple.w b)

One of the things that might not be obvious here is the use of Tuple.x and Tuple.y, etc. These are “accessor” functions that I got for free by using a record data type (Tuple). So Tuple.x a is a function call that returns the x field within a tuple a.

This all seems pretty straightforward and simple, which is what I was hoping for a first chapter. It took me a few hours to “de-program” from Rust, Elixir, Go, bash, Makefiles, and all the other nonsense that was floating around in my head at the time, but eventually the syntax flowed.

One more bit of code that I thought I’d share is a test. Testing is crucial (and easy) in a functional library like this. Here’s how I defined a test for the magnitude function:

test> Vector.magnitude.tests.ex1 = check let

v = Vector.new 1.0 0.0 0.0

actual = Vector.magnitude v

expected = 1.0

actual === expected

The use of the test expression prefix will generate and execute a test. As I’ve mentioned in some previous blog posts on Unison, this test and result are cached and I never need to run them again so long as the code it exercises doesn’t change. In fact, when you run your tests it actually outputs proved, giving you a hint as to the less-than-imperative meaning for tests.

One experience I had that was entirely unexpected was how easy the math was. Floating point math is typically fraught with peril, but the defaults in Unison just work properly. The following unit test would likely create a subspace anomaly if I tried this in another language:

test> Vector.magnitude.tests.ex2 = check let

v = Vector.new -1.0 -2.0 -3.0

actual = Vector.magnitude v

expected = Float.sqrt 14.0

actual === expected

Comparing one value against the square root of 14? Scary stuff that just works in Unison.

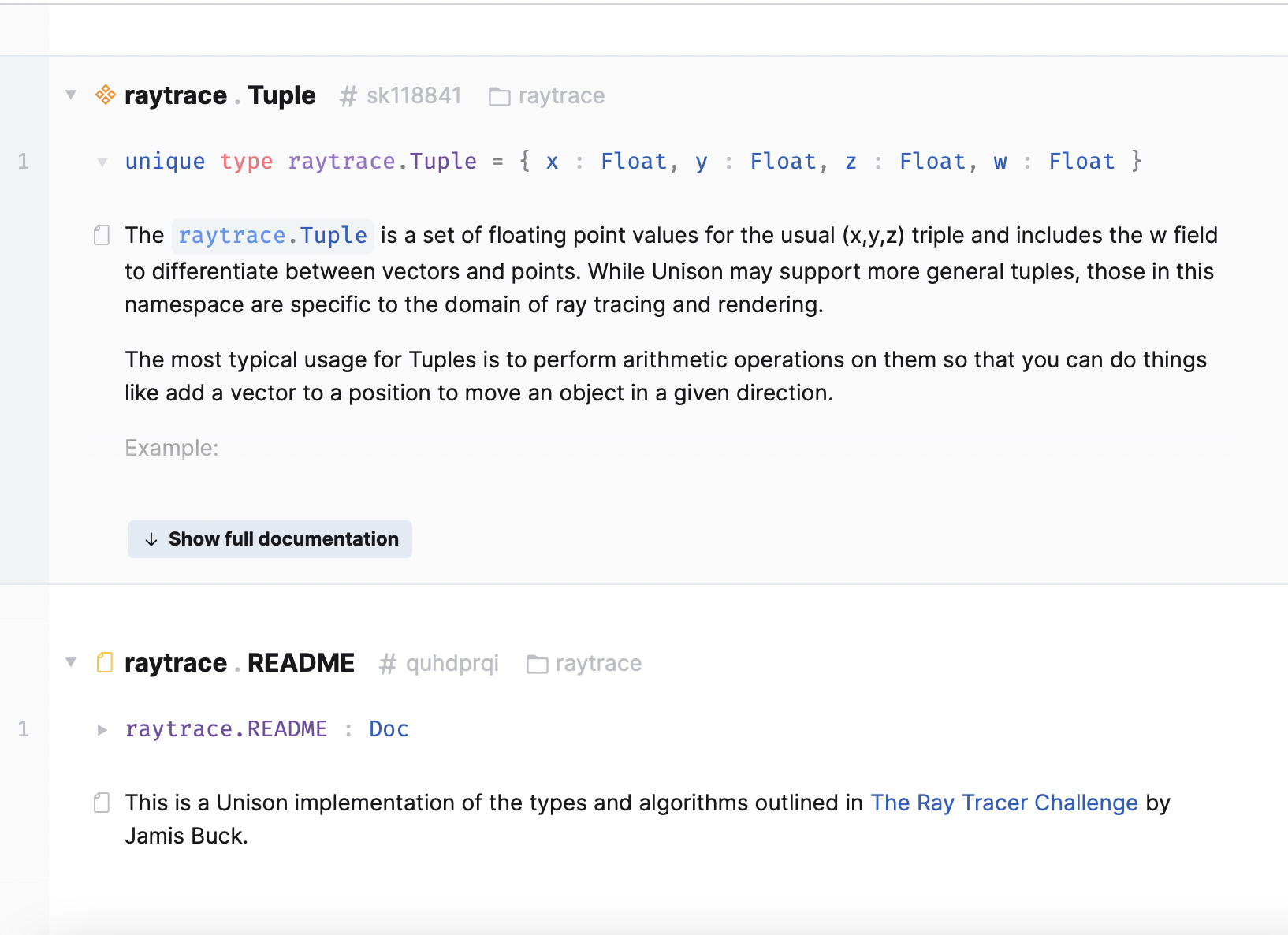

Another cool thing that I’ve mentioned before is how Unison lets you embed documentation directly in your code (like rustdoc). This documentation can contain fully functioning code as an example and the ucm binary even has a function that pops open your documentation in a local “unison share” browser tab:

There is something very tangible about the zen feeling that I get from having clean documentation. It never feels like my code is finished or ready for anyone to use until the code has nice, easy-to-read, easily navigable documentation.

That’s really all there was for chapter 1. In the next post, I’ll be exploring chapter 2 and modeling the Canvas.